Two Washington State cities are looking at guns in ways that may be laying the groundwork for a new attempt to erode that state’s preemption law, a statute that dates back to 1983 and has served as a model for similar laws in other states.

Everett officials are looking at an ordinance that would require victims of firearms thefts to report those crimes within 24 hours or face fines of up to $250, according to KIRO, which discussed this on Facebook and it’s getting a lot of reaction.

My Everett News reported that a Wednesday council meeting will discuss the proposal. Last year, Everett police reportedly investigated 61 stolen firearms cases involving “at least 140 guns.” Police also recovered 27 guns that had not been reported lost or stolen, and so far this year, they’ve recovered nine more.

Guns stolen by burglars are not affected by background check laws when they change hands. Theft is one major source of guns used by criminals, who routinely ignore gun laws across the country. It was one of the principle arguments against Initiative 594, adopted by Evergreen State voters in 2014 as a “universal background check” law that would ostensibly keep guns out of the wrong hands and thus prevent violent crimes. But the state’s two high-profile multiple shootings occurred in 2016, two years after the measure passed, and other violent gun-related crimes have also been committed.

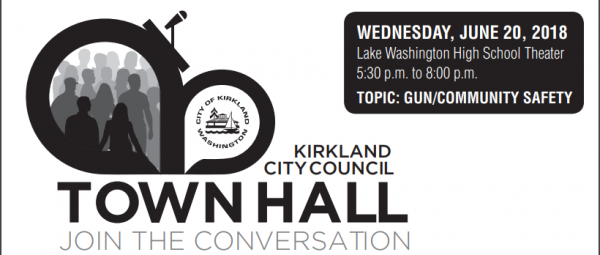

In Kirkland Wednesday evening, there is a “Town Hall” meeting at Lake Washington High School in the theater building to discuss “gun/community safety.” In such conversations, the term “gun safety” translates to “gun control,” say rights activists.

But here’s what the state preemption law says:

“The state of Washington hereby fully occupies and preempts the entire field of firearms regulation within the boundaries of the state, including the registration, licensing, possession, purchase, sale, acquisition, transfer, discharge, and transportation of firearms, or any other element relating to firearms or parts thereof, including ammunition and reloader components. Cities, towns, and counties or other municipalities may enact only those laws and ordinances relating to firearms that are specifically authorized by state law, as in RCW 9.41.300, and are consistent with this chapter. Such local ordinances shall have the same penalty as provided for by state law. Local laws and ordinances that are inconsistent with, more restrictive than, or exceed the requirements of state law shall not be enacted and are preempted and repealed, regardless of the nature of the code, charter, or home rule status of such city, town, county, or municipality.”—RCW 9.41.290

It may be that some cities have been emboldened to try chipping away at that statute because the liberal Washington State Supreme Court allowed Seattle to get away with placing a so-called “gun violence tax” on firearms and ammunition sold in the city. That tax was challenged by the Second Amendment Foundation, National Rifle Association and National Shooting Sports Foundation on the basis that it was not a tax at all, but an illegal fee charged for the exercise of a fundamental right protected by both the state and federal constitutions. As such, it was a gun control law, the plaintiffs asserted, and violated the preemption statute, which regulates all things gun-related, including “purchase, sale, acquisition (and) transfer.”

Seattle and other large liberal-controlled cities in Western Washington have long opposed the preemption act because it has prevented them from creating what would essentially be a hodgepodge of often conflicting gun control ordinances. That was the situation in Washington before the law was passed in 1983 and amended in 1985, and it was why the law was adopted.

The preemption law prevented Seattle from banning firearms in city park facilities.

Everett is also considering an ordinance outlawing the discharge of firearms and even air guns inside the city limits, which opponents have suggested would criminalize self-defense shootings.

If anti-gun politicians can erode Washington’s preemption law, it would set a precedent, and perhaps provide something of a political “road map” for other cities around the country to erode similar laws in their states.