Thursday is the 141st anniversary of a “Wild West” shootout that – while it really didn’t happen in the West at all, but in southern Minnesota – carries with it something of a lesson that may be useful today when a gang terrorizes a community.

The “Great Northfield, Minnesota Raid,” as it has become popularly known, occurred on Sept. 7, 1876. Reminded of the date by anecdotal historian and former Texas Sheriff Jim Wilson, what happened in Northfield could easily be held up as a sterling exercise of the Second Amendment right to keep and bear arms.

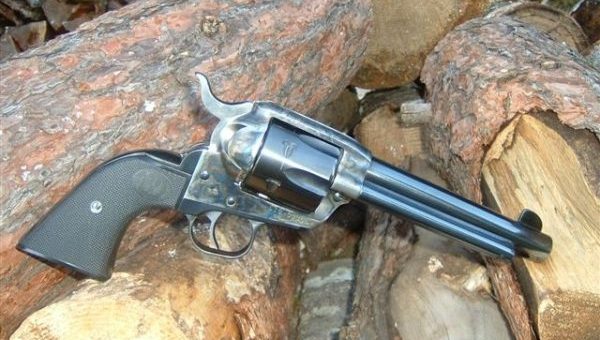

When the James-Younger gang tried to rob the First National Bank in Northfield, instead of getting away with bags of silver and gold, all they got was lead. And most of those bullets were fired by armed citizens who did not care for the idea of having their bank robbed. People protected what was theirs, and they took a dim view of people trying to steal what they didn’t work for while killing innocent people in the process.

The story has been told on film many times, and the wild shootout portrayed on movie and television screens actually did take place. Several people were shot, some of them fatally. Among the dead were bandits Clell Miller and Bill Chadwell. All three Younger brothers – Cole, James and Bob – were badly wounded. In a subsequent gun battle with a posse, outlaw Charlie Pitts was also killed. Frank and Jesse James may have been wounded, but they were the only ones to escape. The outlaw gang was literally shot to pieces.

Bank employee Joseph Lee Heywood and local resident Nicholas Gustavson were also killed.

The year 1876 was an eventful one for Old West history. It was the centennial anniversary of the United States. On June 25, George Armstrong Custer led several companies of the 7th Cavalry down the Montana slopes overlooking the Little Bighorn River and rode into history. On Aug. 2, while playing poker in a Deadwood, S.D. saloon, legendary shootist, scout and lawman James Butler “Wild Bill” Hickok was shot dead.

And then came Northfield. Whatever else the James-Younger gang was, by today’s standards they might be considered terrorists. They were robbers and criminals, and some history suggests they were still sore that the South had lost the Civil War. In recent times, terror attacks in Paris, London, Nice, San Bernardino and Orlando have demonstrated what happens when people can’t fight back to defend themselves and their community. Northfield, on the other hand, was a lesson for the criminals.

Some historians have written that members of the gang repeatedly yelled at people to get off the street, perhaps to avoid getting hurt. Armed townspeople apparently had no such intention.

When people are faced with violence, they can run, hide or fight. Options narrow swiftly when shots are fired and people are killed.

It may not have occurred to the outlaws that their intended robbery victims would fight back so vigorously. Still, this was 1876 and many people still commonly had guns close at hand.

When Charles Whitman opened fire from at the University of Texas in Austin several years ago, killing several people, other Texans reportedly helped keep him pinned down, firing back with hunting rifles. One of those citizens, Allen Crum, went to the top of the tower with Officer Ramiro Martinez, armed with a hunting rifle.

There are some 16.3 million legally-armed citizens who are licensed to carry in the United States. More than a half-million are in Washington, and more than three million are found in just three states, Texas, Pennsylvania and Florida.

In 1876, citizens in Northfield didn’t need licenses or permits. All they needed was to be faced with a threat. It was a hard lesson for the James and Younger brothers, and even harder for the three outlaws who rode with them into Northfield.